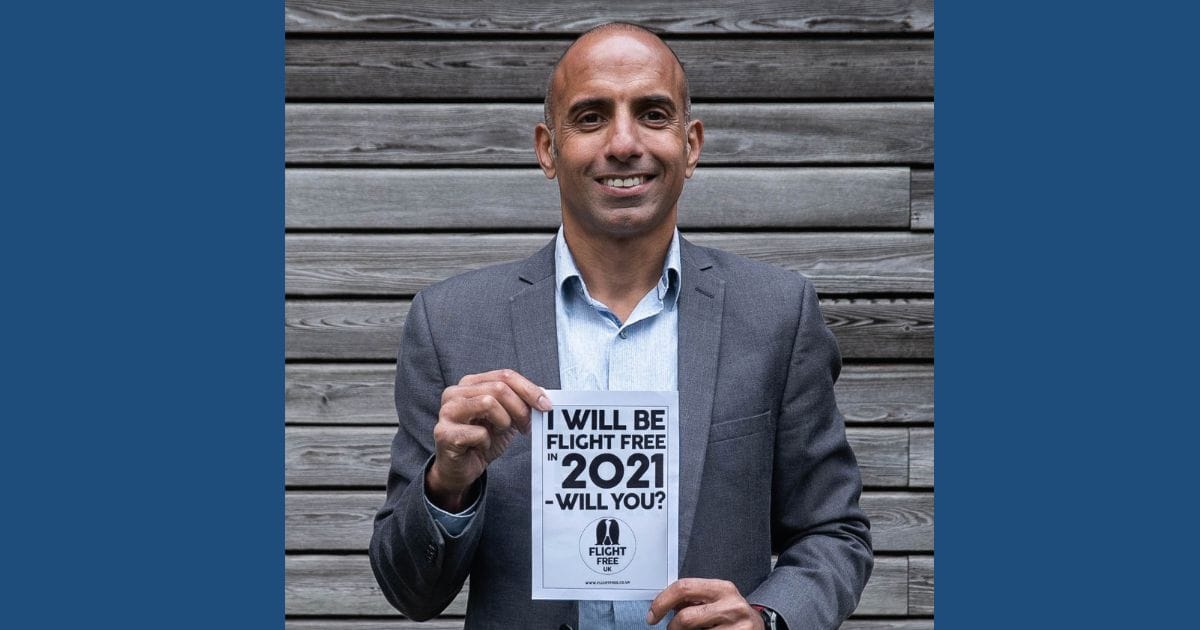

When I took the flight free pledge for 2020, it wasn’t just a personal choice.

All my flights for the previous few years were family holidays, so if I was refusing to fly that would affect my family too.

Like many other people, having a young child sharpened my awareness of climate change. It’s not that I didn’t care about the future of humanity before. But it was more of a vague concern, an unease.

Having a young child sharpened my awareness of climate change.

Once I had a small child, and I took responsibility not only for his safety, but also for his feeling safe and secure, I started to think much further ahead. The year 2050, and even the end of the century, no longer seemed that far away. My unease sharpened into Worry, with a capital W.

I reasoned that people who are seriously anxious about the future should be more willing to make sacrifices. And what parent wouldn’t give up a bit of their comfort today to benefit their child in the future? Sign me up to the climate crusade! But it wasn’t quite that simple.

For one thing, nothing pushes my buttons as a parent more than seeing other people’s children experience opportunities that mine doesn’t have. So alongside my worry about the planet, I had to set my hopes and aspirations for my child. I have enjoyed the freedom to explore the world, so I wanted my child to have that freedom too. If I value curiosity about other cultures, of course I wanted to pass on that curiosity to my child as well. And if other people’s kids are petting turtles on a Pacific island, or flying to Japan for half term (yes, it’s true, I have some very middle class friends) it’s an effort to accept that my family can’t.

But the same applies in the opposite direction: I also don’t want my child to grow up taking flying for granted. I have a friend who took her son on European holidays by train when he was small. Now he is grown up he is a proficient train traveller, an expert reader of timetables, who doesn’t click on the Easyjet web site every time he needs to go abroad. If I bring my child up with interests that can be indulged without flying I’ll be doing him a massive favour.

If I bring my child up with interests that can be indulged without flying I’ll be doing him a massive favour.

And what about my boy – what does he think about it all? Well, being a kid imposes some special issues for going flight free. For one thing, children don’t want to be pitied by their friends for their parents’ choice of holiday. When I was my son’s age I had never been abroad or been on a plane, but that’s not so common now. When we suggest a holiday in Britain, he says his friends will say it is boring. I tell him it’s what you do on holiday that makes for good stories, not where you go.

For another, unlike many adults, children can’t book time off work when it suits their holiday plans. State school pupils in England and Wales are doomed to take their summer break during August, the wettest of the summer months, when it is automatically peak time at any UK holiday destination. If you want to explore a deserted beach with a child in the UK, it’s a good idea either to get up very early or go when it’s raining.

On the other hand, a busy holiday resort, with thriving businesses and other children to play with, has a charm of its own.

My son is also a convinced techno optimist. That’s not surprising, considering that for most of his life he has been reading about the wonder of science.

Plus, until recently, he still believed in magic. He wants to know why planes can’t just use sustainable fuels made from grass cuttings and trash. He has no idea how long it takes a new technology to be deployed in the aviation industry. And in that perhaps he’s not that different from certain leading politicians.

Sadly, he is not quite so persuaded about the power of collective action. When I broke the news that his parents had pledged again for 2021, he cried out ‘But we gave up flying for a whole year and it made no difference to climate change whatsoever!’ Persistence – it’s a skill and an attitude that we both need to learn.

Most significantly of all, it’s not his choice. No longer a small child, and on the brink of becoming a teenager, he wants to do what other kids do. He likes going on School Strike and will enthusiastically wave a cardboard placard. He is not so keen on having his parents tell him what to think, or letting them cramp his holiday style. If I’m to have any hope of him embracing life on the ground, I’ll have to sell it as the rebel thing to do. (I can handle this. I’ve been persuading him to eat his greens for years.)

If I’m to have any hope of him embracing life on the ground, I’ll have to sell it as the rebel thing to do.

I’m determined to do my best to give him a safer world to grow up in. I’ve become a climate warrior, not a climate worrier. And now he is getting bigger, my anxiety about the future is not quite as agonising as it used to be.

Life will be tough, but I’ll have to trust him to make good choices and look after himself and the people around him. Sometimes I think our children are like a message in a bottle to the future. We can’t know who will read our message or even whether it will reach the farther shore.

All we can do is jam the cork in tightly, and throw it as hard as we can to catch the current. And hope that the current is flowing in the right direction.