It can be tricky to bring up the subject of climate change.

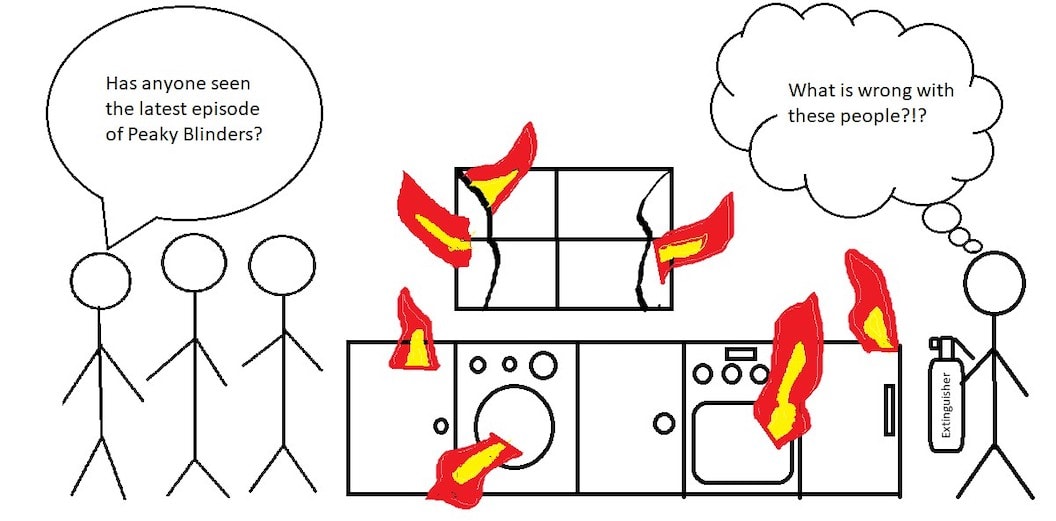

When everyone at a party is chatting about the latest TV drama or the colour of their new curtains, it can be difficult to steer the conversation towards something that is altogether more serious.

If the party were a metaphor for the earth, the entire kitchen would be in flames with the majority of people assuming somebody had left the cake in the oven too long.

So how do we influence those around us? How do we get the people we care about to care about what we care about as much as we care about it?

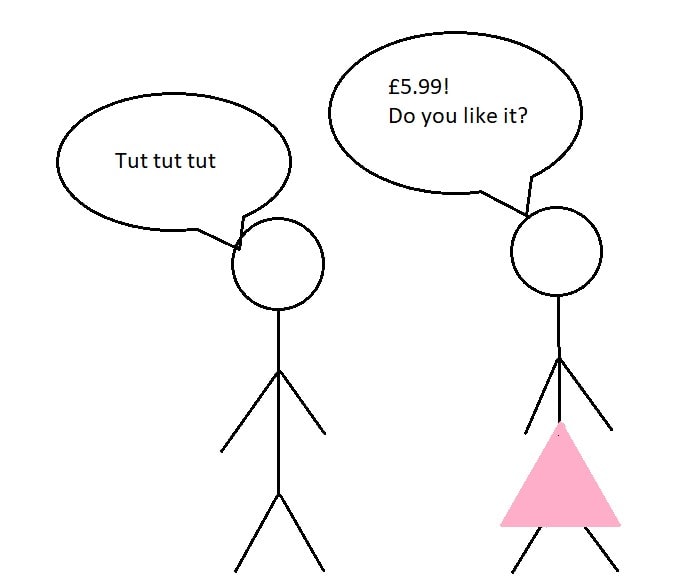

Well, we could start tutting every time we see someone with a plastic bottle, sighing every time they eat beef or huffing every time they start boasting about the brand new dress they got for just £5.99. But that isn’t the best way to win friends or influence people.

We like to think that everyone will act on well-reasoned logic, constantly questioning their actions, but this simply isn’t the case. Humans are social and emotional creatures.

In evolutionary timescales, homo sapiens were recently still roaming the savannah, and in that time, parts of our brains haven’t evolved at anywhere near the pace of the society around us. We spend every day trying to use primitive instincts to navigate an increasingly complex world.

How do we get the people we care about to care about what we care about as much as we care about it?

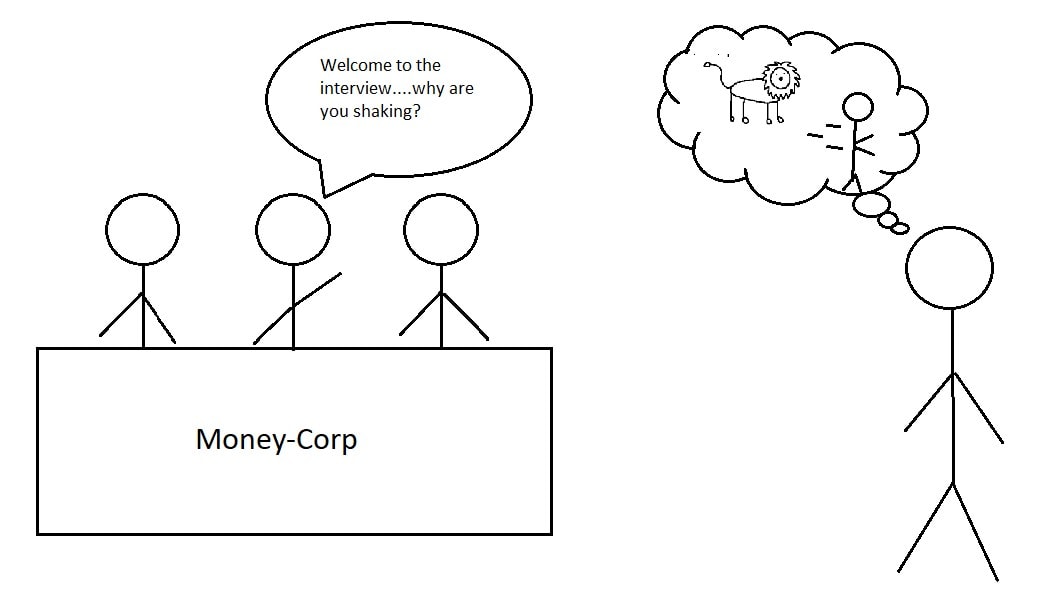

Anxiety is a feeling we all experience, some more than others. But this isn’t a surprise: our brains are still tuned to be on guard for what we perceive as ‘danger’. In the wilderness this might have been a large animal that saw us as prey, or a neighbouring tribe trying to invade our camp. This has now transferred to worries about anything from our health to the thought of being in certain situations which the brain interprets as dangerous. In the wild this would have been extremely useful and often life-saving but the chances of you getting killed at a job interview are usually fairly low.

Other behavioural traits that still manifest themselves today are tribalism and social proof. In the distant past, a tribe might consist of around 50 people and within that 50 we would look to leaders within the group for cues on how to behave. The risk of not following the behaviour of others was high, with the potential of being cast out and left to survive alone, the odds of which were not good.

This can still be seen in today’s society. If your modern-day tribe is formed around a love of watching football and drinking beer at the local bar and you decide actually you would rather watch cricket and drink wine at home, then you will probably find yourself alienated from the group.

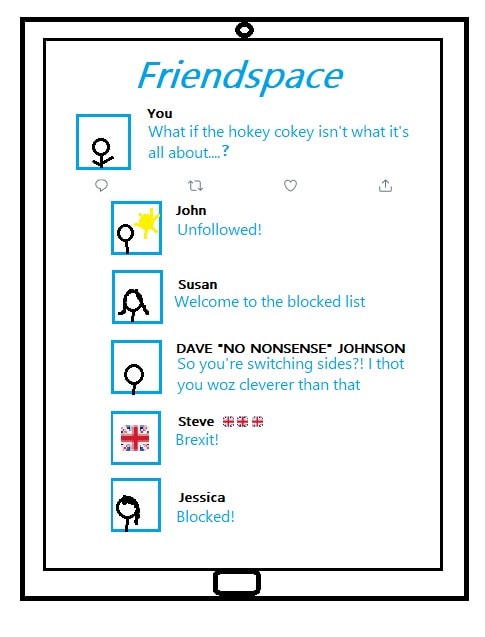

This tribalism can be particularly frustrating in a world which is increasingly centred around social media. Tribes can become huge and built on very simple non-flexible beliefs. Because these tribes are now formed of thousands of people who have mostly never met, it is even easier to be cast aside if you have the audacity to question a belief. With increasing polarisation, it can be hard to find any middle ground.

A solid way to inspire behaviour change is to be a leader – not a leader in the political sense, but someone who sets an example.

Marketers and advertisers have been exploiting this tactic for decades, with libraries worth of literature dedicated to it. A particular favourite in recent times is social proof, which you can observe in the rise of social media ‘influencers’, who might be paid to wear a new pair of trainers or sunglasses so that their millions of followers who look to them for guidance will follow suit.

You might say, “I don’t have a million Instagram followers, who is going to listen to me?” But that is modern day ‘instant gratification’ thinking. We think that if something we say doesn’t go ‘viral’ we might as well not bother. Although there is exciting potential in being able to influence a global audience (as Greta Thunberg is currently doing so well), we can all start small and influence from within our tribe, even if it is just your immediate family.

This is the thinking behind the Flight Free pledge. A pledge is great for making you stick to your promise – studies have shown this to be the case many times. But perhaps an even greater benefit is its use as a conversation starter, a way of saying, “I care about this issue and this is a step I am taking.”

We can all start small and influence from within our tribe, even if it is just your immediate family.

You’d be surprised at the impact this can have. You don’t need to start shouting from the rooftops for the conversations to begin.

Since signing the pledge I have been invited to two stag dos, a wedding and two conferences, all of which are taking place outside the UK, and all of which the default (only) way you are considered to attend is by plane. After signing the pledge every one of these invites is now an opportunity to start a conversation with those in your tribe. The conversation tends to go something like:

“I’m getting married next year in Italy, we are all flying out on the 12th July, you should get tickets for the same flight.”

“Thanks for the invite but I’ve actually signed a pledge not to fly anywhere next year.”

“How come?”

“Well it’s one of the simplest things I can do to cut down my individual carbon emissions and by signing a pledge I am more likely to stick to it.”

“Wow, I knew climate change was a big issue but I didn’t realise flying was so bad, and I also didn’t realise it meant so much to you.”

“I’d love to come to the wedding but I’ll have to explore alternative means of getting there.”

Sometimes this might even result in them signing the pledge too. But at the very least it has planted a seed that will get them thinking.

It can be even more beneficial in a workplace scenario, where people can feel pressure to attend conferences abroad. By approaching your boss and explaining that you would love to attend but have signed a ‘flight free’ pledge, you might be able to get funding for alternative transport. If the company is trying to be more sustainable this is another good conversation starter into why you think staff should not be pressured into flying for work.

And yes, you can share the pledge on social media too and that may have influence, but it is these personal conversations that are where real progress can be made.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think we can rely on individual change alone to save us from the biggest environmental problems we face. I started a podcast for this exact reason. But I do believe that if we have enough leaders who are influencing enough of their ‘tribes’ then the impact can be huge.

Individual change is something we can control, and the choices we make are all votes for the world we want to see.

Rob Wreglesworth blogs and podcasts as 'The Disruptive Environmentalist’. For more stickman-based pieces about the environment head to his website.