I've decided to give up flying, for 2019, for 2020, and who knows… maybe forever.

Over the past few years I have tried to reduce my flights and bought offsets for those flights I have taken. But I now feel that the urgency of global warming is such that relying on offset projects is not a viable response. Planting trees is great. But trees take a long time to grow. Given that there is, at best, little over a decade to avoid catastrophic and potentially irreversible damage to our global eco-system, time is one thing we don’t have.

In the past, I never made the connection between flying – which seemed benign, fun, the gateway to adventure – and pollution. Ignorance was bliss! But thanks to three years of PhD research, I became all too aware of aviation emissions, the pros and cons of carbon offsetting, and the dazzling under-regulation of the air industry.

Learning what I have learnt has made me extremely concerned about our reliance on fast high-carbon travel, and the responsibility of the present generation, and particularly the world’s ‘rich’, to change course. This knowledge has brought its own personal dilemmas.

I became all too aware of aviation emissions, the pros and cons of carbon offsetting, and the dazzling under-regulation of the air industry.

I am an early career academic. Last year I got myself a job as a research fellow, and won funding to carry out a piece of research on how people in China understand issues of environmental responsibility. As the world’s biggest emitter of carbon emissions, and as a society which we in the West still have little understanding of, I think this is an important research topic.

To carry out my research, I need to go to China to meet and interview a wide range of Chinese people in different locations. This is not a topic that I can grasp from my desk at Southampton University.

When I won my funding the assumption was that I would fly to China to do my fieldwork. When I told some of my managers and colleagues that I had made a decision not to fly in 2019 and wanted to get to China by train, I was met with a mixture of responses. Some thought I was mad, some admired my principles, some thought I was being an awkward bugger. Maybe they were all correct. In any case, what I was doing was outside the norm and this decision meant I had certainly created more work for myself.

Although I did have funding to cover research expenses as part of my fellowship, the fact is that trains almost always cost more than planes. As an aside – this is not just because airlines are especially clever and efficient, but is largely because they enjoy tax breaks and subsidies that most industries couldn’t dream of. Anyway, the fact is that my trains cost over £2000, compared to about £600 for a London-Beijing flight (although if I were to fly business class, as many professors would, the cost would be about the same).

To justify this, I had to write to senior managers in the University. I explained that whilst I am not a world-renowned scientist like Kevin Anderson nor a celebrity like our hallowed David Attenborough, I do have some small voice and credibility as a published academic, and my actions ought to reflect my moral and political stance.

That stance is that I believe that flying is highly polluting and criminally under-taxed, and much flying is avoidable and unnecessary. I believe that until low-carbon flight becomes feasible we should all fly much, much less. It would therefore be hypocritical of me to advocate changes for other people that I would not follow myself.

I believe that until low-carbon flight becomes feasible we should all fly much, much less. It would be hypocritical of me to advocate changes for other people that I would not follow myself.

As part of my justification, I pointed to research that shows that climate researchers are taken more seriously if they practice what they preach (who knew!?). If you hear a climate scientist lecturing that we need to reduce our carbon footprint, and then learn that he/she personally flies multiple times per year, you are likely to think that (a) it can’t be all that important; and (b) that your own good behaviour is irrelevant as it will be cancelled out by others’ poor behaviour. That is the classic ‘free-rider’ excuse for maintaining the status quo.

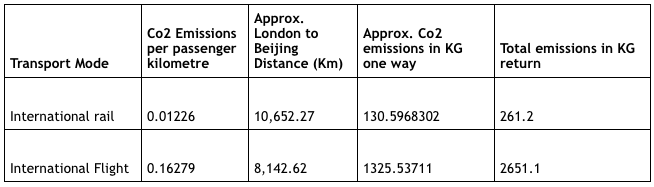

Finally, I added some numbers, which usually helps convince anyone – especially academics. According to DEFRA’s emission factors and my own route estimates, flying from London to Beijing emits about ten times more carbon emissions than the equivalent train journey.

Thankfully I won approval for my train travel, and was left with the minor task of arranging the trains (using an excellent Uni-approved agency), getting visas, completing a risk assessment, arranging insurance etc. It has not been simple. There’ve been times I have found the complexity of itineraries and visas restrictions to be so overwhelming that I’ve almost thrown in the towel.

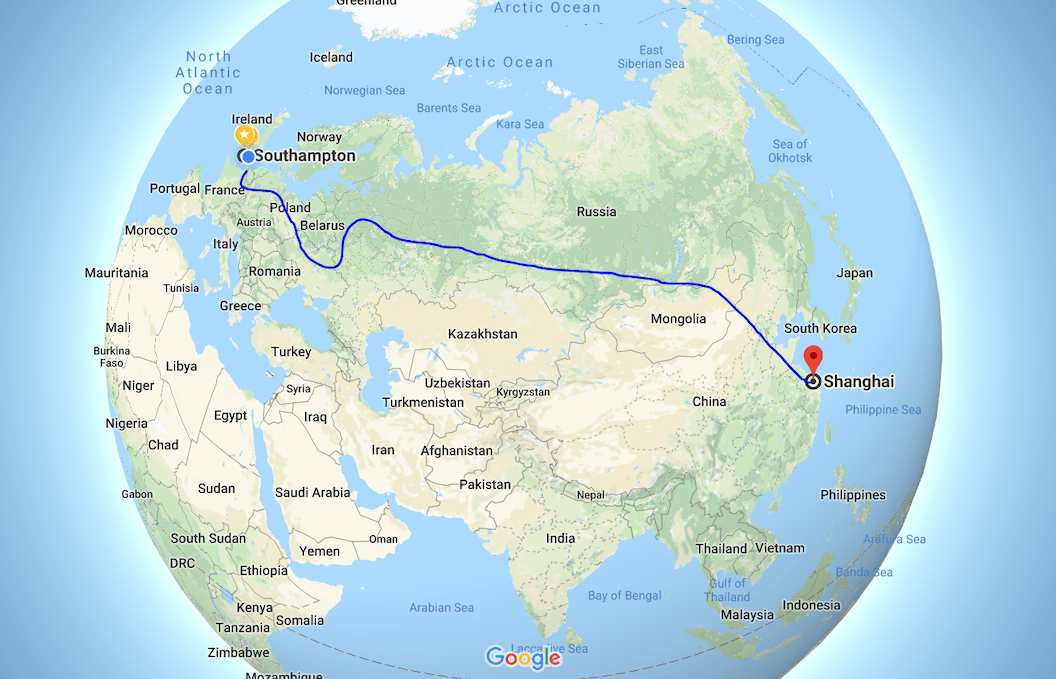

Rather than one ten hour flight to China (requiring only a China visa), my trip will take about two weeks each way, crossing nine countries, using seventeen trains for the round trip, and requiring visas for China, Russia and Mongolia. En route, as well as watching Europe and Asia pass by my window, I hope to use my time to do some reading, and on the way back to start writing up my fieldnotes, and draft research papers. I’m especially looking forward to have an enforced ‘digital detox’, as I don’t think you get Wi-Fi whilst crossing Siberia!

There are, of course, many things that could go wrong along the way, but hopefully I’ll have an interesting and productive trip, which will act as a (rather extreme) demonstration of the possible, for myself and for others.

I admit that my story is somewhat unique and privileged: not everyone can take the train to China for work, and I doubt I’ll make a habit of it.

But I am far from the first ever climate-concerned academic to quit flying either. Within the broader flight-free movement, there is an academic community challenging the assumption that flying should always be the first choice travel mode, especially for well-informed academics who perhaps ought to know better.

We hope that universities will publish records of all staff flights, build low-carbon travel modes into research grant applications as a default option, and build fantastic videoconferencing facilities. Academics should be able to demonstrate to their students, the public, and people in other professions that you don’t always need to fly to be a high-flier.

You don’t always need to fly to be a high-flier.