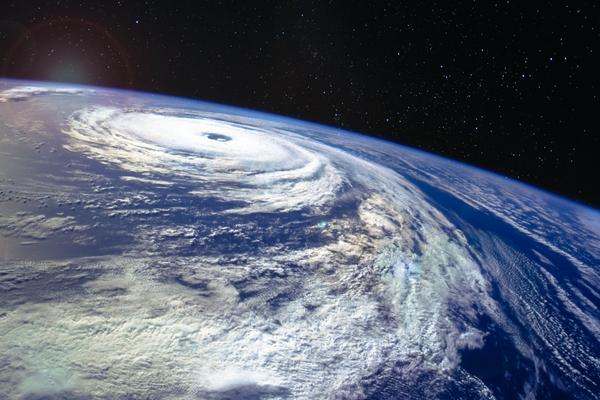

The Conservative government’s Jet Zero strategy was launched in July 2022, on what happened to be the hottest day ever recorded in the UK.

The strategy is the government’s flagship programme for bringing aviation emissions in line with net zero targets.

There are four main strands: Sustainable Aviation Fuel, efficiency gains, new technology, and offsetting. Will the strategy be an effective way to reduce emissions?

Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Sustainable Aviation Fuel, or SAF, is the key part of the government’s plan. It’s the most straightforward way of changing how we fly without actually changing how we fly – we simply substitute one fuel for another. For that reason, the industry is relying on it.

The government and industry claim it can reduce emissions by up to 80%.

We are sceptical about both the savings and the timescale. Our rationale is explained in detail in this blog post, but in summary:

- SAF produces as much CO2 when burned as conventional jet fuel. The ‘savings’ come from the lifecycle of the fuel, e.g. plants absorbing CO2 when they grow, or waste being converted to oil instead of being sent to landfill where it would generate methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Many of these savings claims are questionable, especially when growing biofuel crops drives deforestation – on balance, not very good for emissions.

- Waste cooking oil is already all being used for the road fleet. Using it for aviation would mean diverting it from the road fleet, meaning road vehicles would have to find alternative, probably unsustainable, sources.

- Optimistic forecasts say that we will be using just 5.5% SAF by 2030. Pessimistic forecasts say it will be less than 2%. It's currently less than 1%.

- It is very expensive and will take a long time to scale up.

Efficiency

Better aircraft design and improved ground operations can all contribute to a reduction in emissions. This is good news, until you consider that any savings are typically wiped out with an increase in demand.

For example, going by current improvements, per-passenger emissions could be 36% lower by 2050 – but demand is forecast to increase by 70% in that time.

New technology

New innovations such as using hydrogen and electricity to power planes are being developed. While there is potential for these technologies to substantially reduce aviation emissions, designs are still not close to being ready for commercial use, and now is when we need to reduce emissions.

Even when they are available, we should question if using renewable energy capacity for energy-intensive air travel is the best use for it, when it would arguably be better used in decarbonising our homes, or the road fleet.

Either way, we need to manage demand until the technology is ready. Read our exploration about the limitations of new technology here.

Offsetting

The many issues with offsetting are widely reported, from schemes being ineffective, to there not being enough land space to plant enough trees to offset even one airline’s flight emissions. Mostly, offsets give the impression that our emissions don’t count, so we continue our polluting behaviour.

We explore these issues in greater depth here.

No reduction in flights

This strategy does not take the advice of the government’s advisors on climate change, the CCC (Climate Change Committee), who recommend that managing demand needs to be part of any strategy to reduce emissions from aviation.

The government is very reluctant to do this, with government ministers making statements such as ‘flights are what make life worth living,’ and 'we need to fly more to fund green aviation’. In the Jet Zero plan it explicitly says that the ambition is “to decarbonise aviation in a way that preserves the benefits of air travel.”